Featured in the Fall 2025 newsletter

I was only 30 when my 32-year-old sister was diagnosed with breast cancer. A couple years later, when a mobile mammography bus showed up at my law school offering free mammograms, I decided it couldn’t hurt to be screened. When my mammogram was normal, I made plans to wait until age 50 for my next mammogram. But at age 42, a lump in my breast was detected during an exam, which turned out to be breast cancer. Thankfully, after a lumpectomy and many months of chemotherapy and radiation, I was declared to have no evidence of disease. At this point, my oncologist began recommending genetic testing due to my family’s history of cancer.

For nine years, at every checkup my oncologist would once again bring up the subject of genetic testing. My response was always the same: “I’ll think about it.” But I didn’t. Finally, in 2009, my sister and I agreed to the testing when our mother was nearing the end of her own battle with cancer. We both tested positive for a BRCA1 mutation, and I knew I needed to have two risk-reducing surgeries, a double mastectomy and a complete hysterectomy. However, because I was self-employed, I did not have the time to take off work for two separate major surgeries, so my oncologist worked with me to make sure my one “big” surgery happened. After over 10 hours of surgery, I was stunned to learn the surgeon had unexpectedly discovered I already had early ovarian cancer! I firmly believe that I am alive today because of genetic testing. Had I not learned about MY FAULTY GENE through genetic testing and chosen risk-reducing surgeries, my cancer would have gone undetected until it was too late. I count every year since as a miracle year!

In 2020, I founded the non-profit My Faulty Gene (https://myfaultygene.org) as a way to “pay it forward” for being given the gift of life as a result of my genetic testing. My Faulty Gene is dedicated to helping ensure that everyone who needs genetic testing due to a suspected inherited gene mutation has access to it, because there is power in knowledge! After realizing that patient testimonials are a powerful way to share information, I went forward with a related effort, called Family Gene Share (https://familygeneshare.org), to create short professional videos focused on stories from individuals impacted by hereditary cancers. These videos are gene-specific and were created to help share genetic test results with family members and educate them about the importance of testing and care if they have an inherited cancer gene mutation.

Because educating about hereditary cancer risks is very important to me, I often reshare ICARE’s excellent gene-specific content on My Faulty Gene’s social media platforms. I am also personally enrolled in ICARE and encourage others to join, since I know research is the key to understanding inherited cancer risks and improving patient outcomes. With two of my children having inherited my BRCA1 mutation and with grandchildren at a 50% risk of having the mutation, there’s nothing more important to me.

Sara KavanaughFeatured in the Spring 2025 newsletter

As someone with two inherited cancer gene mutations—MSH6 (Lynch syndrome) and CHEK2 — I know firsthand the emotional and practical complexities of navigating hereditary cancer risk. My journey began without what many might consider “classic” red flags — just a few scattered cancer cases in my family, none of which seemed connected at the time. However, my breast specialist, who takes a conservative approach to patient care, recommended genetic testing to rule out additional risk factors, as I was already considered high risk due to my extremely dense breasts.

That single recommendation opened the door to a journey filled with its share of ups and downs — preventative surgeries, extra screenings, and moments of uncertainty — but ultimately, I am grateful that there have been more ups than downs. Most importantly, it connected me with one of the most supportive communities I’ve ever encountered.

Through it all, I’ve found that curiosity has been my greatest source of strength. The more I’ve learned about my genetic risks, the more confident and in control I’ve felt— with ICARE providing support along the way. What once felt overwhelming now feels purposeful as I manage my care and help others do the same, all thanks to ICARE’s reliable and easy-to-understand resources.

Since joining ICARE, I have been invited to and have participated in the IMPACT Study, which aims to improve how care is delivered after receiving genetic test results. Through ICARE, I’ve contributed to focused research efforts like the IMPACT Study while staying connected to valuable updates that help me — and others — make informed decisions about our health.

One notable example of how this has helped me personally was receiving gene-specific updates when NCCN revised screening guidelines for my CHEK2 variant—a powerful reminder of how critical it is to stay engaged and informed as research evolves. Additionally, the information is so well laid out that I was able to send it to my family members who are interested in learning more while they consider genetic testing.

As a hereditary cancer Previvor, I am honored to support ICARE’s mission, which includes amplifying awareness through my podcast, The Positive Gene Podcast. This platform has allowed me to reach out to others and share important information about hereditary cancer risk, including ICARE’s work. For instance, I recently hosted Dr. Tuya Pal (who founded and leads ICARE) on my podcast, discussing ICARE’s mission to make cancer genetics expertise more accessible—especially for those who might not otherwise have it.

Participating in ICARE is about more than staying ahead of cancer—it’s about working together to empower others. As a podcast host and advocate, one of my roles is to help share valuable resources from organizations like ICARE, so more people feel informed and supported on their journeys. I’m grateful to ICARE for the meaningful work they do every day, and I encourage them to keep going. I carry this spirit into every podcast closing: stay proactive, stay informed, and remember, you are never alone on this journey.

Marleah Dean Kruzel, PhDFeatured in the Fall 2024 newsletter

When I was eight years old, my mother found a lump in her breast – barely noticeable. For a few years, I watched her undergo chemotherapy, radiation, and a prophylactic mastectomy and reconstruction. Since then, my maternal aunt and grandmother also fought breast cancer, and we learned my great-grandmother died of breast cancer at 35 years old.

From a young age, I assumed I would get cancer. That is what happened to women in my family. But those childhood experiences also propelled my desire to give back to the medical community who saved my mom’s life. I earned my PhD and now conduct research to understand and improve communication of cancer and genetic risk information across patients, families, and clinicians.

During my doctoral work, I thought about getting tested. For a year, the test kit sat in my closet because I knew if I tested positive, it would change my life, so I wanted to be absolutely sure I was ready to receive the results. Finally, after my mom and aunt tested positive for a BRCA2 mutation, I did the testing.

After testing positive, I began surveillance, rotating between breast MRIs and mammograms every six months, a regimen I continue. But for over a decade, I have struggled with my uncertain future. One particularly difficult moment was my first MRI after having my son. It had been over a year and a half since I had been screened because I was pregnant and then breastfeeding. The radiologist found something “suspicious,” and I had a biopsy. While I was not diagnosed with cancer, it was in that moment I realized my uncertainty was not going to ever go away. No amount of information would reduce it. No amount of social support would make me feel less alone. So, I did the only other thing I could: I embraced it.

My journey with hereditary cancer has made me realize life IS uncertain. Yet, it isn’t just those with mutations who feel this, but other patients too—a cousin with diabetes, a father with heart disease, a grandmother living with Alzheimer’s. All humans—in all areas of life. But it is in the uncertainty of our lives we learn and grow. Embracing uncertainty means identifying it and moving forward anyways, knowing we will never have all the information to make a decision.

As I reflect on this past decade, in my roles as a patient and a researcher, I can share lessons I’ve learned which help me in my journey. Maybe they will help you, too:

1) Information is powerful, but more information isn’t always better. Trustworthy and credible resources are important to find.

2) Information changes. We live in an era of evolving cancer information. While this is exciting as a researcher, this also means that as a patient, I must continually reassess and talk to my clinicians.

3) Actively participate in medical encounters. Ask questions even when we are embarrassed and bring information to our appointments even when we found them online.

4) Emotions are part of the journey with hereditary cancer. Not only must we manage our own emotions, but our family members’ emotions may also influence us. We don’t always know what someone is going through, so we cut our family slack.

5) Sharing genetic risk information is not a “one and done conversation.” Effective communication with family members requires multiple conversations over years. While we can’t control how our family members react, we can share information in stages to help reduce information overload and to help continue our relationships.

I hope these lessons are helpful and encouraging. May we embrace our uncertainty each day and remember what my mother always says, “We make the best decisions we can with the information we have…at that time.”

Cheryl LivingstonFeatured in the Fall 2023 newsletter

My paternal grandparents were my heroes. Wise beyond their time, they relished teaching our family that knowledge is power, health is everything, and love is unconditional. Back then, Prevention health magazine and vitamin supplements filled their mailbox and 1960’s exercise guru Jack LaLane, and health food advocate Euell Gibbons, beckoned new followers from a talking picture box in the living room. Eavesdropping on adult conversations around their Sunday dinner table was a sport. When their voices lowered, and their eyes bowed, I’d freeze, waiting to hear the word “CANCER” whispered from their tight lips, followed by the name of a person somehow acquainted.

In a blink, my paternal grandpa, who had been a poster child of a life led healthy and clean, was dead from melanoma. Pancreatic cancer swiftly stole the life from my paternal grandma, just a few years later. Looking back at our family tree, both the maternal and paternal branches quivered under the weight of serious cancers – great-grandparents, four grandparents, great uncles, great aunts, father, mother, sister, uncles, aunts, first and second cousins. Cancer had rotted our family tree to the core.

At age 40, my sister (I’m the oldest of four girls), and later my mother, were each diagnosed with lobular breast cancer. Six months after mom’s diagnosis she was gone, having unexpectedly flatlined in the ER, from an unknown cause. One less loved one to break the news to that, only days before, I was inducted into the “you have cancer” club, specifically early-stage ductal breast cancer. Now what? My mind hadn’t considered that my type of breast cancer would be different from theirs. Hoping for better insight, I paid a visit to Vanderbilt’s Hereditary Cancer Clinic.

There, they tested me for many inherited cancer genes, but no BRCA gene mutation was found nor were mutations found in any other genes at this time that would explain the cancers in my family. My sister, who also beat her breast cancer, was proven BRCA negative, back in the day. It’s been suggested she be retested, even for the BRCA mutations again, as much has changed in the past 20+ years, but she has chosen not to test again. There is a weight to knowing some things. Once we’ve opened that proverbial envelope of test results, for better or worse, we are responsible for management and stewardship of caring for that knowledge, for the rest of our lives. So, with much respect, I want to emphasize choosing not to know is also power…and my grandparents would be proud their teachings had not been lost on us.

Adam CampbellFeatured in the Spring 2023 newsletter

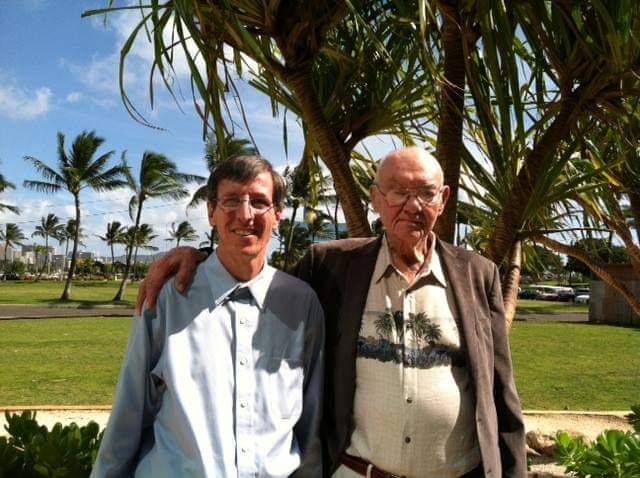

In 1997 when I was a junior in college, my mom called to let me know that my father had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. Luckily for him, Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) testing had recently started which resulted in early detection and subsequent prostatectomy. Due to his diagnosis and knowing prostate cancer is an inherited cancer, my paternal uncle and paternal grandfather began monitoring their PSA levels closely. Over the next several years, both were diagnosed with prostate cancer. As I got older, I knew that I would need to have annual physicals to monitor my PSA levels.

Over the past several years, my PSA level consistently stayed at zero until August 2021, when my PSA jumped to 4.7. To confirm this drastic increase, my primary care physician requested a second PSA. The next day, he called me to let me know that it was 6. Knowing my family history, I felt a sense of fear, but knew there were more steps to be taken before a cancer diagnosis was confirmed. In November 2021, my urologist performed a biopsy that determined a cancer diagnosis. Even though I was destined for this diagnosis because of prostate cancer’s inherited characteristics, my wife Jeana and I were in shock because I was only 47 at the time. Surgery with Dr. Sam Chang took place at Vanderbilt on January 11th, 2022, which resulted in a successful removal of my prostate and a cancer free diagnosis.

With my strong family history of prostate cancer, Dr. Chang suggested that I provide a blood sample for genetic testing. Jeana and I have two daughters, Suzanna, age 17, and Elizabeth, age 12, so we assumed that they would be spared an inherited cancer diagnosis being females. However, after completing my genetic testing and discussing with Dr. Pal, it was discovered that I had a CHEK2 mutation, which can present as breast or colon cancer. We are so grateful to have this important information so we can determine if early testing is right for our daughters.

My father will be participating in testing on April 7th, 2023. He is a retired pediatrician and is eager to be a part of this process to paint a better picture for our family and to help others learn more. My family is so thankful that the Inherited Cancer Registry exists to gather information to assist with cancer research and diagnosis, and ultimately treatment.

Monique Tiffany, MSN, RN, CGRA, BHCNFeatured in the Fall 2022 newsletter

When I was just 8 years old my mother was diagnosed with a very aggressive breast cancer. I didn’t really understand the concept of cancer at that age, but I knew what was happening was terrible. After many surgeries and treatments, she passed away 2 years later at the age of 35. There was no hereditary cancer testing in the 1980’s, but somehow the message came through to me that I too could be at risk. I began having mammograms sometime during my 20’s, even before guidelines were established, and I attempted self-breast exams regularly even though no one really taught me how to. In 2001, at the age of 31, I felt a hard lump in my breast and even before the biopsy came back as cancer, I knew that it was. I was diagnosed with a stage II triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Luckily, by this time testing for BRCA1/2 had become available and thankfully my medical oncologist was savvy enough to know that I needed to be tested. My result came back positive for a BRCA1 mutation, which is associated with a high risk of breast cancer among several other cancers. This changed my world overnight, but also led me to make medical decisions that ultimately saved my life, which is why 21 years later I can write about it here. Unfortunately, I have lost too many close family members to BRCA1-related cancers, but I decided that I am still here for a reason. I decided to go to nursing school to pursue oncology and ended up becoming the lead nurse in a high-risk cancer program in 2009. I enrolled in the ICARE study while attending my first FORCE conference in 2010 and quickly realized that my participation in this study was helping to further research for many other families just like mine. Over the past 8 years I have been working as a Regional Medical Specialist and Nurse Planner for continuing education at Myriad Genetics. I regularly share ICARE research and publications with the healthcare professionals that I work with along with the opportunity to enroll their patients in the study. I love how the newsletters highlight the publications that come from updates from study participants, including my own. I may be just one person but because I attended the right conference at the right time and made the right decision to take a proactive role in helping others with hereditary cancer, I have been able to affect thousands of patients. That has given me an amazing sense of purpose with a disease that seems so purposeless.

Stefanie Curtiss & Meghan DurrickFeatured in the Spring 2022 newsletter

Genetic testing sounded like a futuristic concept when it originally came to our attention. It sounded something to the likes of cloning. We didn’t really understand what it was and why it was important, but rather thought it sounded like something out of science fiction. Thankfully, our medical providers and genetic counselors stuck with us until we understood the benefit.

Growing up, our family was blessed and untouched by cancer. We didn’t have any immediate family members treated for or diagnosed with cancer in our childhoods. We were familiar with the term cancer but didn’t know what it MEANT. That all changed in our early 20s when our mother was diagnosed with uterine cancer. She had already been through menopause and therefore knew when she had bleeding that something was wrong. We often wonder what would have happened if she had been younger when the cancer occurred, and she didn’t have that indicator?

Thankfully, our mother was an employee at Vanderbilt, where she was referred to the genetic department for genetic counseling and testing and was diagnosed with Lynch syndrome due to an MSH6 mutation. We met with the genetic counselor at that time who did a great job in explaining what it meant if we had a mutation and encouraged us to get tested. This was in the early 2000s, when testing was thousands of dollars; and we were also worried that if we had the mutation, it could be considered a pre-existing condition for insurance companies. These concerns and being frightened to hear we were potentially predisposed to cancer led to our decision to not move forward with testing.

Our mother battled her uterine cancer and recovered. Later, she was diagnosed with kidney cancer and even later still melanoma. This temporarily caused us to bury our heads in the sand even further. However, eventually as our 20s turned into our 30s we realized this was something we shouldn’t ignore. Insurance now covers the testing. Law states that you can’t consider it a pre-existing condition. Our excuses were being removed and we decided it was time to move forward and see if we also had the mutation. Stefanie was the first to meet with the genetic counselor. Testing was so easy, they used saliva, so no blood was even needed to be drawn. Shortly after, the results came in that Stefanie had inherited the MSH6 gene mutation from our mother. Being identical twins, Meghan knew she also had this mutation, even before she was tested mainly as a formality.

Although the initial diagnosis of having an MSH6 mutation was scary, we realize it is scarier not to know. Since the diagnosis, we are now screened every year with colonoscopies and kidney screenings because of our family history. We both recently had our uterus and ovaries removed preventatively. We have an older sister who recently decided she also wants to get tested. We are so grateful and feel at peace that we can be prepared to minimize the impact any potential cancer diagnosis has on our lives thanks to our doctor’s monitoring and care. If cancer shows up, we are now READY!

Stefanie now has two workshops a year on the benefits of genetic testing. Meghan now acts as an advocate for those who don’t have access to affordable healthcare and/or are afraid to explore their medical needs.

Dan Dry Dock ShockleyFeatured in the Fall 2021 newsletter

At the age of 51, my first and only colonoscopy revealed 100 polyps in my colon, rectum, and anus even though I had no symptoms or family history. I was immediately referred to a Certified Genetic Counselor at Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawai’i. Germline DNA testing revealed I had attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP), due to an autosomal dominant germline mutation. After reading about AFAP to better prepare myself and learn the facts of AFAP, I wanted to have the surgery to remove my colon.

I embraced this diagnosis from the onset and have since joined various registries focused on inherited cancers, participated in live-case presentations, and have been selected to serve on advisory boards. Sharing my journey and being a source of inspiration is important to me. Shortly after my diagnosis, I created my mantra: Always Forge Ahead with a Purpose. This is a positive spin on a bleak diagnosis. My mindset is not to think of things I’m unable to control, such as medical conditions, but what I can control is my positive attitude. My vision is to establish national legislature jurisdiction designating the 4th week of March as Hereditary Colon Cancer Awareness Week. As of this year, Texas is the only state to designate this Awareness Week.

My purpose in life now is to educate the world about AFAP and the importance of early detection in hopes of saving lives, continuing the legacy of Dr. Henry T. Lynch.

Dave DubinFeatured in the Winter 2021 newsletter

My genes don’t define me. I am AliveAndKickn. Pretty bold statement. AliveAndKickn is more than just a name. It’s a way of life. I joke that Lynch Syndrome is the genetic predisposition to colon cancer, endometrial cancer, other cancers…and soccer. But that’s just me. Besides half a dozen surgeries since 1997, I have and still play and coach the game I love. You may find your own game, or hobby, or solace in something that can help you in your day. Lynch Syndrome, other hereditary cancers, even other disorders are difficult to absorb and overcome. Having your first colon cancer at 29 is not easy. Surviving (thus far) to a point where your oldest son who has inherited your mutation is 25 is also stressful. The fact that my father, grandfather, and brother have all lived long fruitful lives post-cancers is comforting to both me and my family. Knowledge is power. By knowing you have Lynch, you can stay ahead of your cancer.

As co-founder of AliveAndKickn, I’ve had the good fortune of being able to share our message with a number of outlets, including the Forbes Healthcare Summit and the Biden Cancer Initiative, and more. AliveAndKickn has co-signed on a number of grant applications for studies, and has had posters at ASCO, NSGC, CGA and other professional conferences. AliveAndKickn is here for you. We are looking to make a difference for you and others, both current and future with hereditary cancer. Part of that is helping navigate the system, offer insights into options, share a smile, look for research trials, but most importantly, aggregate pertinent data to research potential cures. Genetics is taking huge strides almost every day. Precision medicine, immunotherapy and gene sequencing are the future. We thank you for being a part of our lives. I’m humbled to be part of yours. Be resilient. Be AliveAndKickn!

Kristin Anthony

Featured in the Summer 2020 newsletter

PTEN is one of the body’s tumor suppressor genes, which controls cell growth. When a PTEN mutation is present, cells may grow uncontrollably, causing tumors to develop that may become cancerous. A patient born with a PTEN mutation is at high risk for developing breast, thyroid, kidney, colon, and endometrial cancer. My PTEN journey began after being diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2009. This diagnosis, along with breast health issues and a family history of breast cancer, raised health concerns prompting me to consult a skilled genetic counselor where I learned I have a rare and underdiagnosed disease known as Cowden Syndrome or PTEN Hamartoma Tumor Syndrome (PHTS).

I was relieved to have a diagnosis yet overwhelmed about what would come next. Since the diagnosis, I have had two melanoma removal surgeries, a preventative hysterectomy, and preventative mastectomies. I also have annual colonoscopies due to polyposis (a PTEN outcome) and preventive kidney screenings. With hereditary cancer syndromes, it’s essential to stay a step ahead; knowledge is power. I found that many physicians in my community had very little understanding of Cowden Syndrome and that getting a diagnosis is difficult. That, coupled with lack of educational information about PHTS, motivated me to start the PHTS Foundation in December 2013. I want people to know that if they have a large head and family history of cancer or autism, that is enough to consult their physician for PTEN testing. Patients are their own best advocates.

As a three-time cancer survivor and President of the PHTS Foundation, I work to raise funds for PHTS research and educate the public about PHTS. In my role, I am a twice-nominated Global Genes Champion of Hope, a top 10 Wego patient leader hero, and an inaugural member of Alabama’s Rare Disease Advisory Council appointed by Governor Ivy. I was invited by Europe’s Orphanet group to provide PHTS expertise for their disability project, and consistently work to advocate for PTEN families and all in the rare disease and hereditary cancer community by speaking about the importance of the patient experience and lobbying for policies that will benefit patients and families affected by genetic cancer syndromes. I am fortunate to have received top-notch care thus far, including current care by Dr. Galen Perdikis and the VUMC Breast Center care team for recent breast implant removal to DIEP breast reconstruction.

Featured in the Winter 2020 newsletter

I was diagnosed with breast cancer in December 2018 and was found to be PALB2+. The PALB2 gene had not been tested for when my older sister was diagnosed with breast cancer and had genetic testing done four years earlier. This was new! My cancer was very similar to my sister’s, but being PALB2+ changed my treatment plan and informed me of my possible higher cancer risks for recurrence and other cancers. Like my sister, I had one small tumor in one breast. I could have just had a lumpectomy with radiation and chemo (depending on ONCA result) followed by oral medication, and then just live with a risk of recurrence. The other treatment option was a skin saving, nipple sparing bilateral mastectomy with FLAP reconstruction followed by 5-10 years of oral medication. This would have reduced my risk of recurrence to below 10%. It was a no brainer for me — I chose the latter. After my breast surgery, I was then told PALB2 was linked to ovarian cancer, so I started seeing a high-risk gynecologist. After months of discussions with my gynecologist and oncologist, I decided to have an oophorectomy. This was prompted by my PALB2 risk and my adverse reaction to Tamoxifen. The only way to get off the Tamoxifen was to put me into menopause by removing my ovaries, which at the same time, would lower my ovarian cancer risks. Again, this was a no brainer. It’s two years after my diagnosis, and I’m in a really good place. My cancer is nearly behind me, as I don’t think about it on a daily basis. I’m feeling great and look even better 😉 My energy levels are back to normal, I’m playing competitive tennis, and I’m spending time with my family traveling and enjoying life. We look to the future with positivity. We know there is a chance that I have passed the mutation onto my three kids but we feel empowered by the knowledge of knowing about it, and we will test them for it when they get older. My family is empowered too. We recently found out that my mother is PALB2+. Great news, she’s 75 years old and has never had breast cancer! So PALB2 doesn’t necessarily mean a cancer sentence! I have personally known many family and friends diagnosed with breast cancer; my best friend being one who was diagnosed 8 years ago with stage 4, triple positive, metastatic inflammatory breast cancer. She has had radiation, chemo, had her spine rebuilt, and been on numerous clinical trials. She is here today, and her tumor has shrunk by 67%. What I learned from her: “Always have a note taker with you at EVERY appointment because there is always too much info to absorb. Don’t ever give up and never let it define you. Fight your battle your way. And when you need it, ask for help.”

Featured in the Summer 2019 newsletter

Life was great at 45. I had nothing more than a few headaches and was a tad overweight. After a friend was diagnosed with breast cancer, I realized I had not had a mammogram in a couple of years, so I scheduled an appointment. One mass was found, but it was benign and nothing to worry about. The mass continued to grow, and again, a biopsy confirmed it was benign. The mass was removed, and I went on with my life. A few months later, I returned for a follow-up appointment. It felt like a blow to my chest as the doctor confirmed I had a rare malignant phyllodes tumor in one breast. Because of the rarity of this type of cancer, I was offered genetic testing. A few months later, I was diagnosed with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (due to a TP53 mutation), a rare condition that greatly increases the risk for many types of cancers.

I have three children ages 11, 22, and 27. My 11-year-old was diagnosed with autism at age 3, which has prepared me to advocate like no other. Although there is so much more to my story, when faced with challenges, I prefer to come through and share the answers I have collected throughout my journey. I’m just starting, but here are a few tips I have used to cope:

- Brainstorm your thoughts in a journal. I have learned there are so many things I can’t control, but so many more that I can.

- Get your life in order and encourage your family and friends to do the same. With or without Li-Fraumeni syndrome, we are all guaranteed a death which can happen at any moment. As crazy as it sounds, while journaling, I realized that death was not my real fear. My real fear was leaving my son, and what his life would look like if I was not here to take care of him. Insurance policies, wills, trusts, and written expectations for my son are no longer something just on a to-do list.

- Get organized. I’m still figuring this out, but the appointments and test results can take over your life quite literally. Getting a calendar and establishing systems that work for you is a must.

- Research solutions and take an active role in your care. Ask questions no matter how silly they may seem. Always ask, “Is that the best we can do, and what are my other options?”

- Take your time when making decisions. Never allow anyone to pressure you into making a decision. Sometimes you have to take a step back and seek wise counsel.

- Create a “worry” section in your journal. As things pop up in my mind, I write them in the “worry” section of my journal and tell those thoughts that we can talk about them later during my worry time. “Worry time” is time I set aside to worry so that my day is not consumed with worry, which helps me stay focused on positive things. Typically, by the time “worry time” comes around, I have either found a solution, or I’m over it!

- This probably should have been number 1 on the list but seek therapy. A few weeks in I realized the thoughts about “what if” were consuming me. Depression is real. Get a good therapist. It may take several sessions with several therapists but talking it out can be a game changer.

Hope this helps because I’m out of space. Sending great vibes and love your way!

Featured in the Winter 2019 newsletter

When I was 50 years old I was in pretty good physical shape and I thought I was finally getting six pack abs. I was wrong – those abs were a large football sized tumor, along with a variety of smaller tumors. I was diagnosed with Stage 4 ovarian cancer. I had a hysterectomy and fibroid removal when I was 40 years old, but we left the ovaries because of my age – if only I knew then what I know now.

My mom died of adenocarcinoma (lung cancer common in non-smokers) at 62 years old. My middle sister had Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in her 20’s (twice)! My dad (a few years after donating bone marrow to my sister – he is a hero) was diagnosed with Post-Polio Syndrome and Multiple Sclerosis – and that is just my immediate family’s medical history! Based on this and my personal history, genetic testing was a no brainer for me. It turns out I carry the BRIP1 gene. My youngest sister decided to have a hysterectomy with her ovaries removed at age 47 after learning about my genetic test results – if she had to do it over again, she may have had genetic testing of her own and regular screenings instead (because menopause is not fun).

I am grateful to be able to share this information, especially if it can help protect future generations. It took very little effort to get genetic testing and if I can help a family member (or anyone for that matter) by sharing my genetic makeup, it is the least I can do to contribute to the prevention and early detection of cancer. To me, genetic testing is a way for me to help someone else. If there is a possibility of treating, preventing, or curing cancer, I am all IN – take all the blood, genes, and body parts you want!

I am not sure how or why, but I am one of the lucky few. I know a lot of women are in a constant battle trying to get where I am – 4 years with no evidence of disease (NED). I will do anything I can to help, and I am grateful to the scientists and doctors working so hard to find a cure or better ways to detect cancer early.

Featured in the Summer 2018 newsletter

I was aware from a very young age that breast cancer was part of our family. I knew that my great-grandmother (whom I never met) had breast cancer and my grandmother was diagnosed in her 50’s. While I didn’t grow up being afraid of the disease, I was far more aware of it than were any of my friends. My mom was diagnosed with a uterine sarcoma in her mid-40’s and breast cancer at age 48, and again at age 54. She underwent a few grueling surgeries, but was spared chemotherapy and radiation. She also had her ovaries removed prophylactically, years before it was considered a “viable” option. My grandmother died in her 70’s from complications of ovarian cancer, and my mom lived until she was 81 when she succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease.

When I learned about genetic testing for the BRCA genes in spring of 2000, my mother and I had testing through Vanderbilt’s genetic counseling program and learned we were both BRCA2 positive; my two sisters tested negative. After much research—I met with numerous oncologists, surgeons, and plastic surgeons, and learned everything I could about possible insurance ramifications to any decisions I might make—I decided to have a complete hysterectomy and a prophylactic bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction.

During this time, I turned to FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered) for much of my research and critical emotional support. My family was extremely supportive; my husband was “all in” despite having no prior experience with cancer. I felt lucky to have three healthy children (ages 3, 6, and 9 at the time) and was ready to undergo these surgeries to lower my cancer risks. The surgeries didn’t scare me because I had watched my mother successfully undergo tough surgeries. Primarily, I was afraid of the unknown.

It’s been 17 years since then, and I have no regrets. I’m eternally grateful for the research dedicated to hereditary cancers, the familial support I received, and the peace of mind my surgeries brought. I participate in ICARE and other related activities in hopes that continued research will positively impact all of us with hereditary cancers, and especially my three children who are now young adults. From my mom, I gleaned two thoughts I hope I’ve passed on to my children: live every day to the fullest; and knowledge is power. Because of my mother’s legacy and willingness to tackle this very tough issue, my kids are armed with information they can use as they grapple with difficult decisions in the years ahead.

Featured in the Winter 2018 newsletter

A cancer diagnosis is a life-changing event for every patient and their extended family. However, how we respond to this diagnosis is as individual as our very existence as evidenced by our looks and personalities. Following my diagnosis of stage 4 prostate cancer in 2014 at age 54 which had spread to my bones, I was initially crushed, especially when I found out that I was in the very small percentage for whom there really was no cure. I then did what I always do, just like I did when my son with Down’s syndrome was born – I tried to gather all the knowledge to make the best decisions to move forward. As with my son, who is now a 22 year old with a loving personality and working, my goal is to pursue the best outcome possible.

With a background of many immediate and extended family members with cancer, the decision to do genetic testing was easy, through which I found out that I was positive for the BRCA2 genetic mutation, which was not very surprising. Since all four of my children are now young adults between 21-33 years old, we had a great discussion about future testing and what this means. To my knowledge, none of them have completed testing yet, but they have all been like their old man…happy to have the knowledge to help them make good decisions on their own future preventive care. I am also personally glad they are armed with good information.

As for my own future, so far I am exceeding expectations. The first treatment was expected to last 18-24 months, but mine lasted 40 months! Now moving into what is called “advanced prostate cancer” I continue to be happy that my quality of life is still good. I also continue to rest in my faith and trust God for whatever future that remains.

Featured in the Summer 2017 newsletter

After a long rainy summer filled with doctor visits, I was finally diagnosed with triple-negative inflammatory breast cancer (TN IBC) at the age of 49. I completed treatment in June 2008 and was grateful to have a new phrase to my vocabulary – NED, ‘no evidence of disease’. Since there was no cancer history in my family tree, genetic testing was not offered to me. Fast forward to 2013, with a stronger knowledge base of BRCA gene testing, my medical team suggested I be tested and I agreed. My test results revealed that I carried a BRCA1 mutation, which meant that my children could have the gene as well. I strongly feel that any tool that can be of help to my family to be educated is important, as well as helping medical advancement. This testing could let my children and grandchildren know if they are at risk for breast and ovarian cancers. My three daughters subsequently had testing and my oldest daughter, Natalie, was also found to have this mutation. As Natalie has so eloquently stated after finding out, “I’m glad I’m armed with this knowledge so I can make informed decisions.” [https://www.theibcnetwork.org/moms-daughters/]

After my diagnosis of IBC, I was shocked at how little information was available regarding this type of breast cancer, and even more shocked at the lack of research and education considering it was first written about in the 1800’s. I formed the IBC Network Foundation, to encourage education and fund research for this orphaned form of breast cancer. I am pleased that we have managed to put almost 1 million dollars to research in five years. Our impact is now global, as we also have a sister charity in the UK funding research.

Vanderbilt is a leading cancer center, but I became familiar with some interest in TN IBC over a chance meeting with some researchers at a conference. I was pleased to see their passion and therefore saw the need for funding. Our foundation has committed to funding TN research at Vanderbilt.

Upon learning about the Inherited Cancer Registry (ICARE) based at Vanderbilt, I was excited to join to contribute to the research mission, as well as being given the opportunity to receive regular research and clinical updates. As much as it might seem frightening to some to join a registry like this, I am grateful for the opportunity to help pay it forward by supporting inherited cancer studies in the hopes we can all live well and have long healthy lives.

Featured in the Winter 2017 newsletter

On my 43rd birthday I was diagnosed with an advanced stage breast cancer. Although my BRCA1 and BRCA2 results were surprisingly negative, I was certain there must be a genetic component to my breast cancer since I was diagnosed at a fairly young age. I remained in contact with my geneticist, Dr. Georgia Wiesner, and in 2016 she suggested I have more genetic testing for inherited breast cancer through a multi-gene test, which wasn’t available in 2011 when I was initially diagnosed. As a result of my additional testing performed through Dr. Wiesner, I found out I was positive for the CHEK2 mutation which not only explains my personal history of breast cancer but affords me the knowledge of additional screenings I may choose to have in the future. There was not a lot of information on the CHEK2 mutation and I found myself very fortunate to find a closed support group on social media for women and men that have also tested positive for a CHEK2 mutation (Facebook CHEK2 Mutation Support Group). I subsequently brought a family member to Moffitt for testing, at which time I came to know about and enroll in the Inherited Cancer Registry (ICARE) and am passionately dedicated to helping find answers with regards to how our genes may play a significant role in our cancer diagnosis and potentially our clinical outcome.

If you are interested in joining this CHEK2 support group on Facebook, simply search for “CHEK2 Mutation Support Group” and request to join. As this is a private group, moderators will screen individuals who request to be added to the group.

Featured in the Summer 2016 newsletter

When I was diagnosed with cancer the first time at age 38, my sister (a breast cancer survivor since the age of 29) was positive we had a BRCA gene mutation. However, after we both had genetic testing done in 2006 the results showed we didn’t. Doctors said they were surprised we did not have a mutation in one of the BRCA genes, but believed we probably had another gene mutation that was not yet identified. In 2011, we were asked to participate in a genetic study called Whole Genome Analysis of High Risk Cancer Families through the Genetics Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We both had our DNA sequenced and were found to have a mutation in the PALB2 gene. The genetic study asked if other family members would be willing to be tested and out of the 19 members tested, 18 were positive for PALB2. Since my second battle with breast cancer this past year, I am more committed to help in whatever way I can help find a cure and find answers as to how our genes play a crucial role with cancer.

Featured in the Winter 2016 newsletter

I was first diagnosed with breast cancer when I was 56 years old. Because of my strong family history of breast cancer, I was referred for genetic counseling and had BRCA testing at that time. Recently, I was diagnosed with breast cancer again. When I went to see my surgeon, she advised me to have more genetic testing for inherited breast cancer through multi-gene tests, which were not yet available when I first had my testing. Through this testing, I was found to have a PALB2 gene mutation, which explains my personal and family history of breast cancer. I recently enrolled in the Inherited Cancer Registry, as I am interested in participating in research in any way that I can to learn more about inherited cancers in people with a PALB2 mutation.